The Invisible Hand Needs a Hand: Two Short Vignettes on Market Design

Top Choice

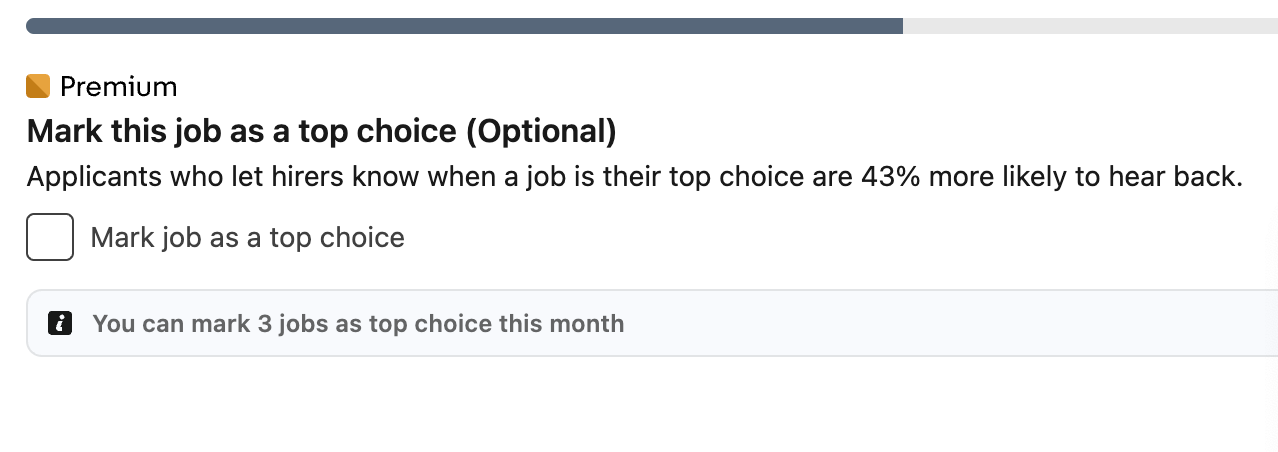

On LinkedIn (Premium?), users can mark up to three jobs per month as a “Top Choice,” making them 43% more likely to hear back. (Note: Given that the relevant base rate is likely close to 1%, a 43% relative increase means going from 1 to 1.43 per 100.)

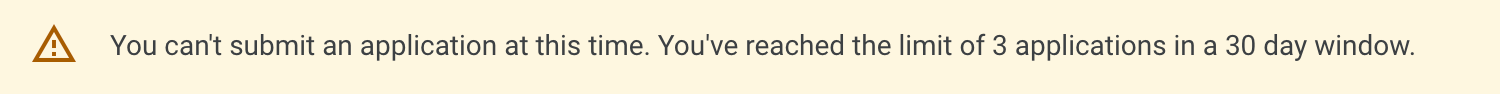

Google's restriction on applications is another solution for reducing congestion. Google limits applicants to three applications per 30 days.

The features draw on work by Alvin Roth, Peter Coles, Alexey Kushnir, and Muriel Niederle, among others, on solving congestion in markets. The basic idea is as follows: when everyone applies to everything, employers are flooded. Employers struggle to separate desirable and interested ( 'attainable' in the language of Coles et al. 2013) applicants from desirable applicants who are just hedging. (This is often why employers have a recruiter screen.) Limiting applicants to just three expressions of interest means each expression of interest is informative and reduces evaluation burden by directing the firm's attention to genuinely interested candidates.

The downside of these solutions is that applicants make these decisions with limited data, and considerations like risk aversion, etc., may mean that the final matches (after accounting for assessment costs) are worse than the status quo. (In Google's case, applicants may not even know about the clause till they hit the limit.)

Could we improve matching by letting applicants pay for review, as some economics journals do? In balanced markets, most decisions are made at the margin. If the cost of misclassification is higher for the applicant than for the employer, then letting applicants pay for more accurate classification could increase welfare. A yet better solution may be centralized testing like the hard-to-game certification exams run by major software companies like SAP, Microsoft, Google, etc.

Batch Feedback

Airbnb’s mutual blind review system was meant to encourage honest feedback: neither guest nor host sees the other's review until both are submitted. In theory, this deters retaliation. In practice, it leads to soft coordination and inflated ratings.

Over time, users adapt. Guests and hosts coordinate via direct messages. What emerges isn’t truth—it’s a 4.8-star détente. Even when retaliation is off the table, social costs remain. Giving a negative review feels personal. Without anonymity, honesty declines. The result is reputation inflation.

A better alternative is batch-aggregated reviews, where individual feedback is anonymized and combined into rolling averages and thematic summaries. This design lowers the emotional cost of honesty, discourages strategic behavior, and surfaces more accurate signals about quality. It shifts the review process from a personal exchange to a shared informational asset—harder to game, easier to trust.

p.s. My notes on Alvin Roth's dissatisfying book, Who Gets What —and Why: The New Economics of Matchmaking and Market Design, on market design.