Advertising Without Signal: The Rise of the Grifter Equilibrium

Economists credit ads with two welfare‑enhancing roles:

- Informative – trimming search costs (Stigler 1961 (pdf)).

- Signaling – In classic models, high-quality sellers are more willing to incur large, sunk ad costs because they expect to recoup them through future sales, especially in experience-good markets where quality is learned over time (Nelson 1974). Milgrom and Roberts (1986) formalize this idea: when ad spend is costly and more valuable to better firms, it can serve as a credible signal of quality.

The Internet upended the first role—search is instant—but also weakened the second.

Five Frictions That Flatten the Signal

- Disposable brand identities

Launching a fresh storefront requires packaging, photography, and a seed set of paid or incentivized reviews; yet, those outlays are tiny relative to the lifetime margin on a successful listing. Because tarnished names can be retired cheaply, long‑run reputation no longer disciplines bad actors. - CPA pricing removes the burn

Most major ad systems now let advertisers pay only when a sale or lead occurs (Target CPA in Google Ads, Cost‑per‑Result goals in Meta’s Advantage+ campaigns, goal‑based bidding in Amazon DSP). With spending converted from sunk to variable, even low‑quality sellers can fund promotion from day one revenue. - Light‑touch returns & the “Frequently Returned” tag

Seamless returns cap consumer harm, but seller penalties are modest: a restocking fee, a metrics ding, or Amazon’s “Frequently Returned Item” badge—issued only after damage is done. Only the worst lemons are fully delisted, leaving plenty of mediocre goods in play. - Ratings compression

Star ratings on major platforms increasingly cluster between 4.3 and 4.9, leaving buyers little room to distinguish products. Part of this stems from review manipulation—Amazon blocked >250 million suspected fake reviews in 2023 alone, indicating the scale of the problem. - Heuristic‑driven shoppers

Deprived of credible signals, buyers default to the price–quality heuristic—higher price means better goods (Monroe & Krishnan, 1985). Sellers respond by listing identical inventory at staggered prices across multiple storefronts.

These frictions reinforce one another: CPA funding keeps every storefront bidding; fake reviews mask quality gaps; disposable brands dodge reputational blowback; and behavioral heuristics close the sale, locking the marketplace into what we call the grifter equilibrium.

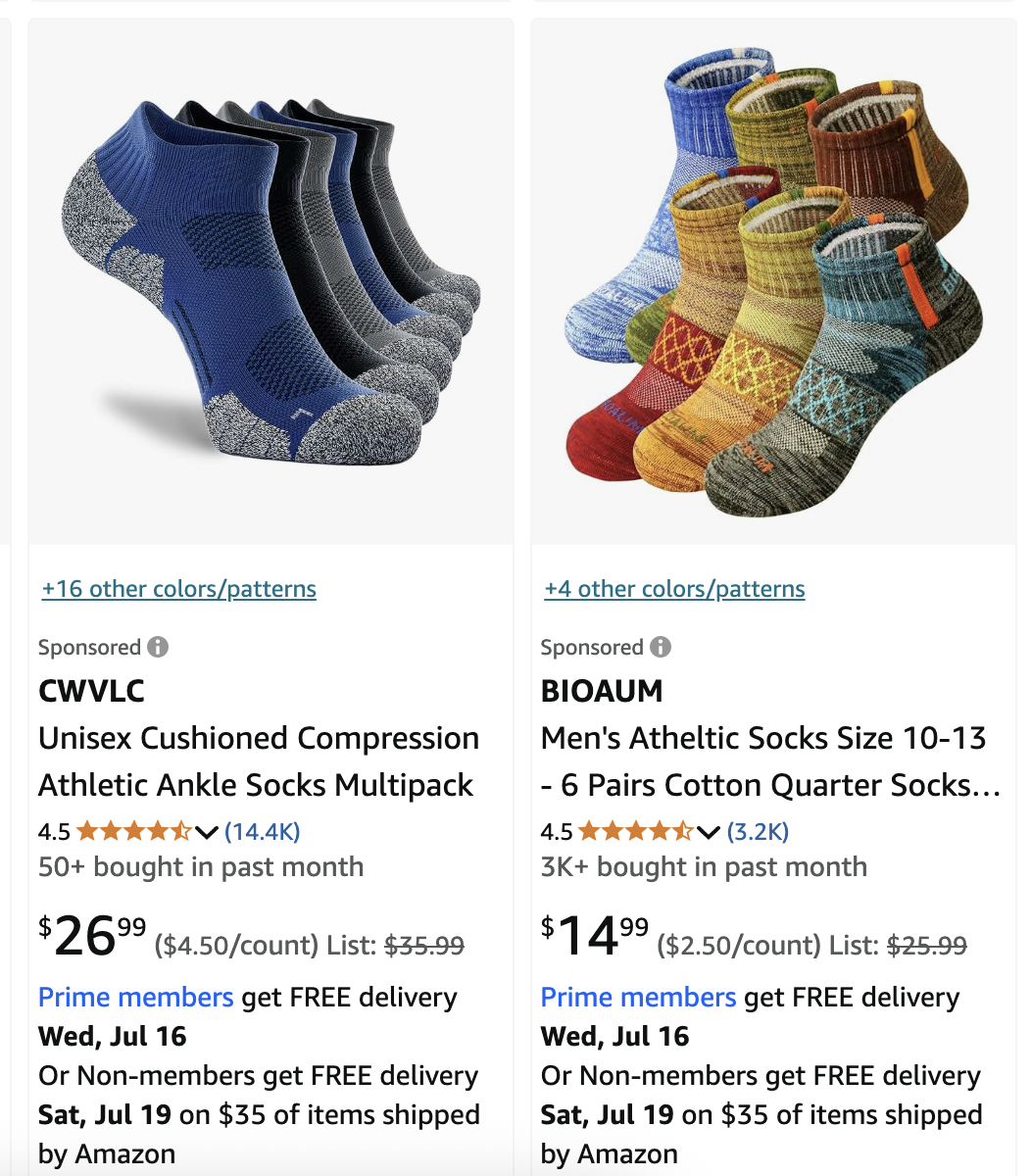

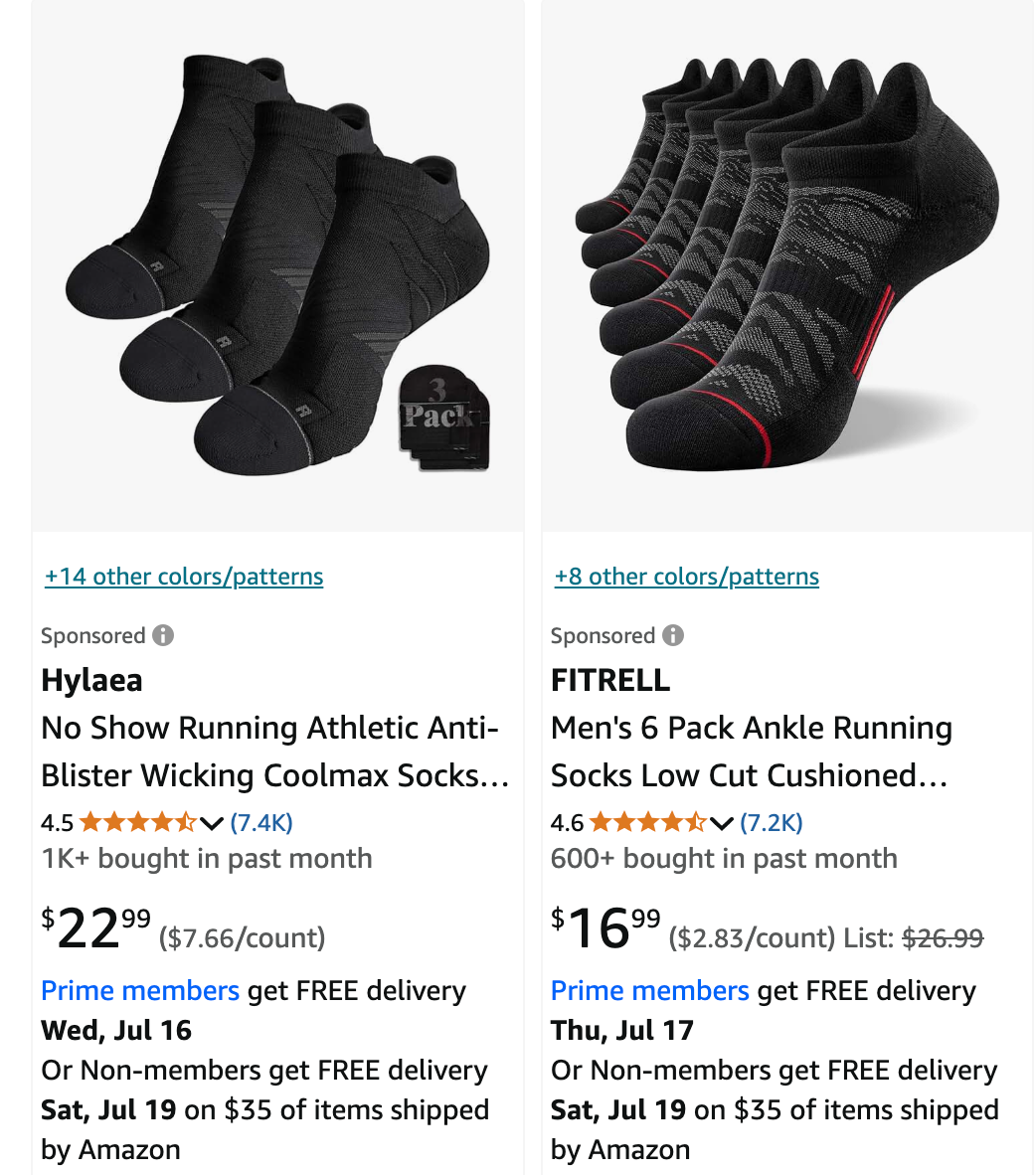

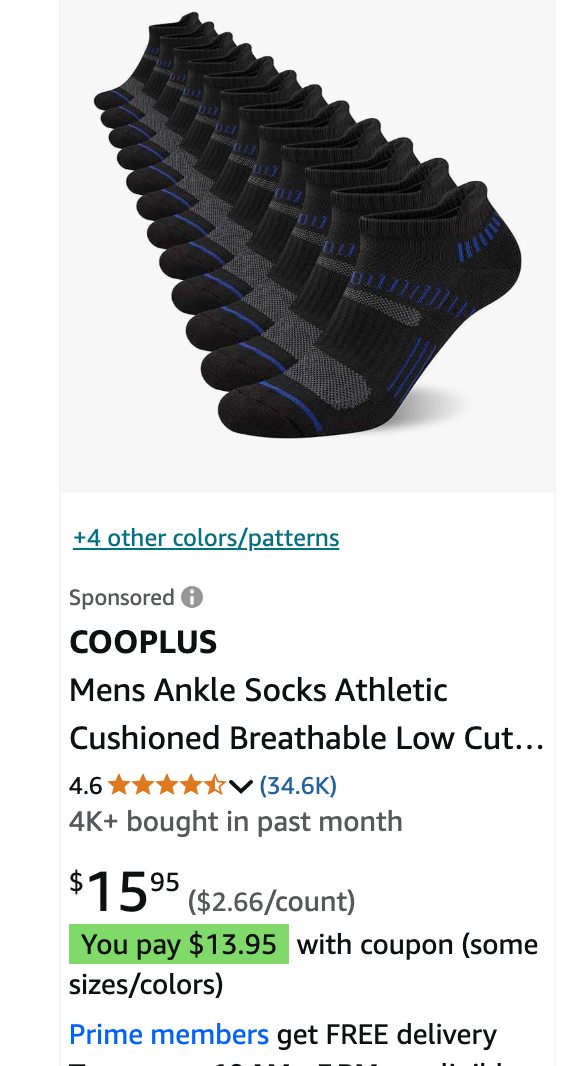

A Sock Search in Action

Search “ankle socks” on Amazon:

- Sponsored slots dominate; brands are unfamiliar.

- Ratings hover around 4.5; product photos are interchangeable.

- Prices span a wide range without visible changes in features.

Formalizing the Grifter Equilibrium

A. Parameters and Properties

| Symbol | Domain / Constraint | Key properties |

|---|---|---|

| $p$ | price | — |

| $m_H,m_L$ | unit costs | $m_H > m_L$ |

| $\tau$ | CPA take‑rate | — |

| $\theta$ | traceability level | $\theta \in [0,1]$ |

| $\phi(\theta)$ | lemon‑detection hazard | $\phi'(\theta) > 0$ |

| $R$ | penalty per flagged lemon | — |

| $k$ | relaunch cost (new brand, etc.) | — |

| $\lambda$ | repeat‑purchase rate (Poisson) | $\lambda > 0$ |

| $r$ | continuous discount rate | $r > 0$ |

| $C(\theta)$ | fulfillment / storage cost | $C'(\theta) > 0; C''(\theta) \ge 0$ |

| $L(\theta)$ | lifetime value preserved | $L'(\theta) > 0; L''(\theta) \le 0$ |

B. Per-sale margin (before penalties)

$$\pi_H^{\text{base}} = p(1-\tau) - m_H$$

$$\pi_L^{\text{base}} = p(1-\tau) - m_L$$

C. CPA vs. CPC

Expected ad cost per sale = $\tau p$.

With CPC, expected cost = $\frac{c}{q}$ where $c$ is the bid and $q$ CTR; a mistargeted campaign can burn capital before a sale. CPA caps spend at contribution margin:

$$\tau p \le p - m_L$$

Thus, lemons can never bankrupt themselves by over-bidding; they simply hit zero margin.

D. Seller NPVs

High-quality, with repurchase loop:

$$\text{NPV}_H

= \pi_H^{\text{base}}

\left(1+\frac{\lambda}{r}\right)

$$

Low-quality (storefront dies upon detection):

$$\text{NPV}_L = \frac{\pi_L^{\text{base}}}{r + \phi(\theta)} - \frac{\phi(\theta) R}{r + \phi(\theta)} - k$$

Lemons never enjoy repurchases ($\delta=0$) because the brand resets.

E. Who advertises?

$$\pi_H^{\text{base}} > 0, \quad \pi_L^{\text{base}} > (r+\phi)k + \phi R$$

If price nets out between these hurdles, only lemons advertise.

A pooled advertising equilibrium exists whenever

$$\pi_H^{\text{base}}>0 \quad\text{and}\quad \pi_L^{\text{base}}>(r+\phi)k+\phi R$$

so both seller types buy ads, yet advertising fails to signal quality because

- CPA pricing makes the per-sale ad cost the same fraction τ for every seller;

- Penalties are limited — low values of $\phi, R, k$ keep $\text{NPV}_L>0$, letting lemons profit even after restarts;

- High-quality sellers' higher cost $m_H$ raises their threshold, but not enough to exclude lemons.

When these conditions hold, buyers face indistinguishable 4.5★ ads.

F. Why the Platform chooses $\theta^{*}<1$

Let $\theta \in [0,1]$ (0 = commingled, 1 = fully segregated).

$$\Pi(\theta) = L(\theta) - C(\theta)$$

• $L(\theta)$ = trust/lifetime value saved by blocking counterfeits, $L' > 0$, $L'' \leq 0$

• $C(\theta)$ = extra fulfillment cost (scans, bins, routing), $C' > 0$, $C'' \geq 0$

FOC (maximize Π): $L'(\theta^*) = C'(\theta^*)$

SOC / shape: beyond $\theta^*$, $C'$ outruns $L'$ ⇒ interior optimum.

$$\theta^* < 1 \quad \text{because } C'(\theta) > L'(\theta) \text{ as } \theta \to 1.$$

Low marginal benefit + rising marginal cost ⇒ retailer stops short of full traceability. Commingling remains the low-cost local optimum.

Escape hatches

- Authenticated Fulfillment Tier – Upload lot serials; scans at inbound/outbound; brands allowed Buy-Box gating. → ↑ $\theta$, ↑ $\phi$ → Control over Buy-Box + co-op ad rebates offsets fear of channel conflict.

- Return-adjusted CPA (R-CPA) – $\tau_i = \tau + \lambda(\text{return}_i - \text{median})$. → ↑ $R$ proportionally to bad CX → Honest brands see no fee hike.

- Escrowed ad bonds – 15% of ad bill held; forfeited if $\phi$ exceeds threshold. → big ↑ $R$ → Lump-sum hurts serial relaunchers most.

- Persistent manufacturer IDs – Brand ID required for new ASIN; penalties follow factory. → ↑ $k$ → Legit factories gain protected shelf space.

- Listing-history diff tab – Expose every image/title change; ML flag drift. → ↑ consumer info, ↓ fake-review ROI → Good brands get transparency halo.

Raise any of $\phi$, $R$, or $k$ far enough and $\text{NPV}_L$ flips negative → lemons exit.

Why the Marketplace Doesn't Implode

- Return valve caps but doesn’t erase consumer pain.

Generous return policies and Amazon’s “Frequently Returned Item” badge let buyers jettison the worst lemons. Hassle costs remain, but catastrophic disutility is rare. - Ultra‑low unit costs keep lemons profitable.

When socks cost $2 to make and the CPA take‑rate is 20 %, sellers can survive double‑digit return rates and still clear margin. - Heterogeneous, often low‑stakes demand.

For gym gear, kids’ camp supplies, or one‑off gadgets, shoppers accept higher quality uncertainty in exchange for speed and price, muting the penalty for mediocre goods. - Platform revenue is tied to congestion, up to a point.

Amazon collects a fee on every ad click and every sale, so a crowded, ad‑dense marketplace boosts short‑run revenue. The company does police egregious abuse to protect long‑run customer trust, but the optimal balance still tolerates a substantial volume of “good‑enough” products.

See also: https://www.gojiberries.io/optimally-suboptimal-behavioral-economic-product-features/